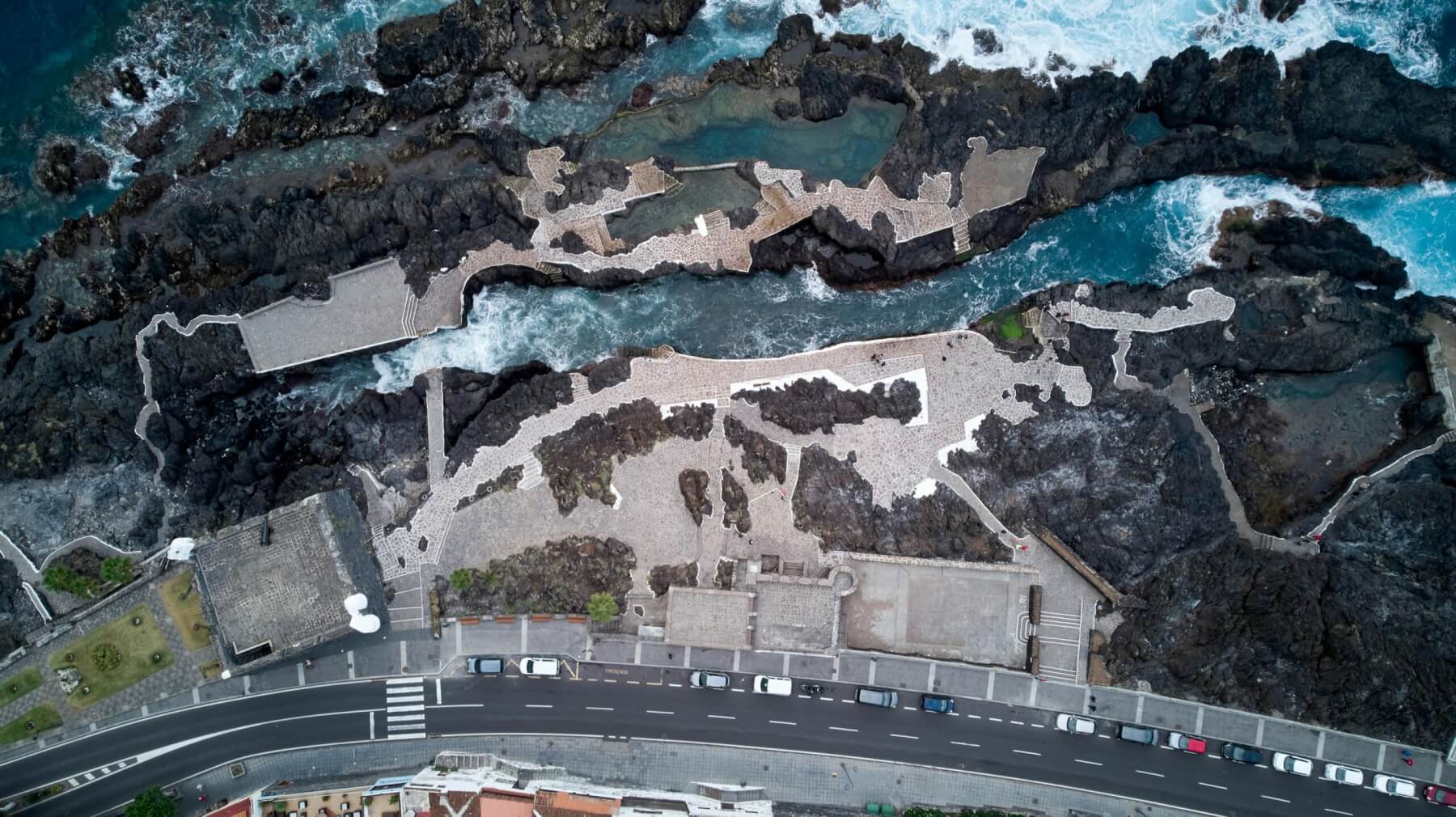

Garachico, Spain. Photo: Florian Eckerle

People around the world are often familiar with the most significant eruptions, such as the 1883 Krakatau eruption, which had profound and far-reaching effects. However, there are many stories of volcanic eruptions that have impacted communities globally, yet remain underreported or have been lost to time.

As part of my ongoing work in the Canary Islands, a volcanic archipelago off the northwest coast of Africa, and a region of Spain, I am collaborating with partners at GeoTenerife to help provide locals with insights into their volcanic history. It is crucial that we continue to raise awareness of these historical events and their relevance to present-day communities.

This has led me to explore 18th and 19th-century Spanish eruption accounts. These accounts offer invaluable glimpses into past volcanic activity, which can help us recognise how unrest and eruptions might impact communities. This, in turn, can critically assist with decision-making when a volcano stirs.

One notable example is the 1706 eruption in Garachico, on the northern coast of Tenerife. At the time, Garachico was the island’s largest port and was a thriving town with smaller villages nearby. During this eruption, lava cascaded down the steep slopes into the town, partially filling and damaging the harbour. Despite its relatively small size compared to other eruptions, this event had a profound impact on both the town and the island as a whole.

Constructing a reliable eruption timeline from historical records is challenging. Our modern understanding of volcanic processes has evolved and the terminology we use today often differs from that of the past. For instance, interpreting terms like “smoke” (Is it ash? Gas? Steam? Or something actually burning?) or “fire” (Is it lava?) can be difficult. A deep understanding of volcanic activity is essential to making sense of these descriptions. Additionally, translation errors can further complicate matters. For example, translating “lahar” from Indonesian as “cold lava” is misleading—cold lava is simply rock.

However, these historical accounts also offer us crucial insights into volcanic precursors, especially during times before the advent of modern volcano monitoring.

One colourful account reads: “tombs could be seen as if they were trying to throw out dead bodies, and in the houses, the roofs began to shake until they gave way. The bells could be heard ringing with heartfelt blows, as if they were ringing in agony…” (Cassares, 1709). Along with other historical eruption accounts, this suggests that seismic activity can be a significant precursor to eruptions in the region.

Other accounts provide a window into the emotional experiences of the people living through these events, such as: “the fearful night continued… in this way, Lord, the great earthquakes originated, with such ferocity that everyone was moved to sadness.”

Learning about past eruptions is essential for preparing communities for future volcanic events. Each volcano presents unique lessons, shaped by its specific landscape, history, and the culture of the people living in its shadow. By examining these stories, we can better equip communities to face the challenges posed by future eruptions.