A very important part of volcano monitoring is understanding seismicity, meaning earthquakes or vibrations that move through the Earth that we sometimes feel at the surface. Most volcanic earthquakes are too small to be felt by us, but seismometers record them and capture valuable information.

Lava from volcano. Photo by Brent Keane.

Geophysicists are the experts who study these phenomena and untangle the sometimes very complex signals to unravel clues about what is going on below the surface, using their expertise, experience, and technology. Just to be clear, I am not one of these experts.

Janine Krippner

When there is an increase in seismicity at or near a volcano, an important start is figuring out what the cause is. Is it volcanic or not? It could be magma, fluids, gases, or faults. Volcanoes are often located in areas with plenty of faults, so earthquakes could have nothing to do with the volcano itself. They can also be produced by shallow geothermal activity, which is likely what those in Taupō were feeling a few weeks ago. When they are near the surface and close, they can feel more intense.

If something is moving below the surface, it could be magma, fluids, or gases. Fluids can be a mix of water and other components like CO2 that are released from magma. It can take time and hindsight to work through the signals to understand what caused them.

Earthquakes can be classified into types, given a magnitude, and a location including depth. Here is a very simplified guide.

Volcano-tectonic (VT) earthquakes occur when rock breaks. This can be through faults moving because of tectonic forces or migrating magmatic fluids and gases putting stress on them from a distance, or magma and gases breaking rock as they move.

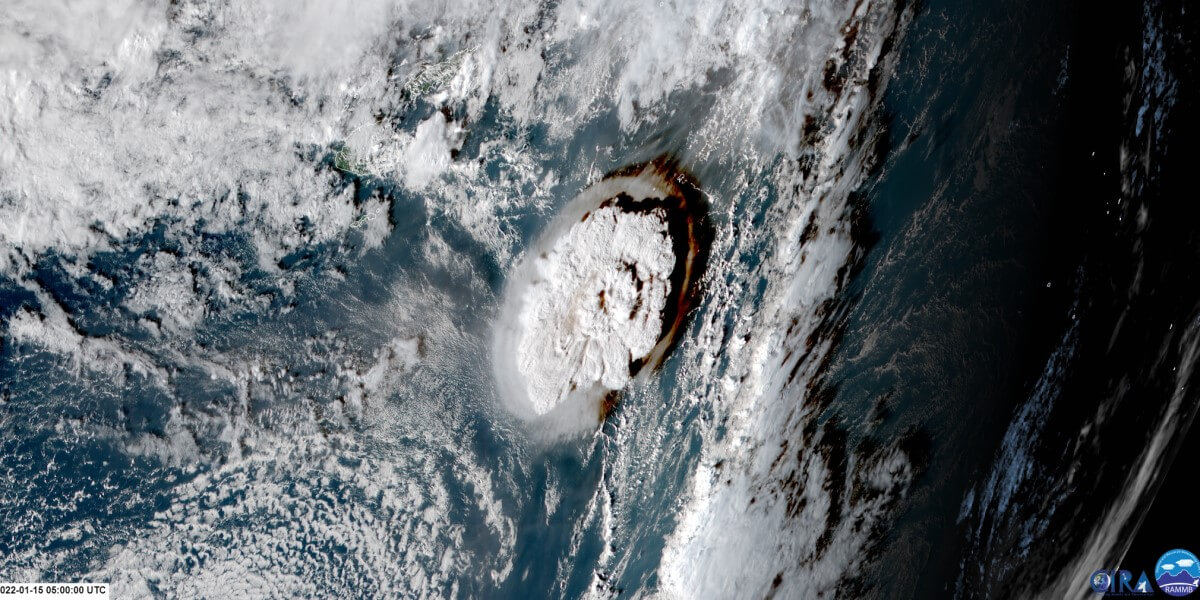

Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai eruption in Tonga

As magma, fluids (magmatic or hydrothermal), and gases move through cracks they can produce long-period (LP), very-long-period (VLP), or low-frequency (LF) earthquakes. This can be a sign that magma is on the move, but not necessarily.

Tremor is a continuous seismic signal that can indicate that the volcano means business with magma moving or an eruption is even underway, or that there are so many earthquakes that it’s hard to distinguish between them all.

Keep in mind that many processes can produce signals at once This includes ‘noise’ at the surface like animals or human activity, or other natural processes like wind, landslides or waves. We need our seismologists around to figure it out!

Since seismicity is a normal part of being a volcano, active or not, it’s important to know what the “background” or usual level of activity is so that we know when something is changing. Incorporating other data such as gas or deformation (movement of the surface), also helps to clarify what’s happening down below.

While these earthquakes are usually small, they can also be very harmful, especially when people live close to where they are originating. As Taupō has seen in the past, seismicity during volcanic unrest can be damaging even without leading to an eruption. Shaking can cause building damage that can result in injuries, or trigger landslides, which can sometimes even lead to a tsunami. It is always important to be prepared and know what to do in our volcanic areas, so be sure to visit getready.govt.nz for more.

Photo: Eriks Cistovs: pexels.com