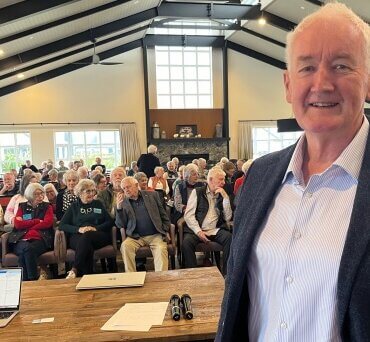

Russell Snell

The benefits of advanced genetic research in identifying disease pathways and developing treatments was outlined at a recent talk in Cambridge.

Genetic research. Photo: Thirdman: pexels.com

New Zealand geneticist Professor Russell Snell’s talk to Cambridge U3A focused on trials being done on two neurodegenerative diseases, Alzheimer’s and Huntington’s Disease.

In both cases, researchers here and in Australia have tapped into sheep, primarily because their large, complex brain structure assimilates more closely to humans than do the brains of mice. Their longer lifespan is also an advantage.

Snell, who was born in Feilding and raised in South Otago, studied physics before completing his PhD in genetics in Wales in 1993. He is now with the Centre for Brain Research at Auckland University where his area of research is the identification of the genetic basis of diseases, and in the use of genetics in New Zealand’s agricultural sector.

Huntington’s and Alzheimer’s diseases are inherited, but the disease progression and age of onset is often determined by other factors.

Everybody inherits the Huntington’s gene, he said. Scientists have discovered that when that gene is faulty, the protein it produces repeats certain genetic sequences known as CAG at an increased rate. This faster repeat sequence appears to damage neurons in the brain, leading to the development of symptoms.

Experiments involving sheep have shown the presence of elevated levels of urea and ammonia in Huntington’s patients, leading to current research being done in both the brain and the liver, where urea and ammonia are produced.

“Most people working on Huntington’s are working in the brain. We are a bit of a contrarian and are looking at both the brain and the liver,” Snell said. “It is very much a work in progress at the moment.”

Sheep are also proving to be key to research around Alzheimer’s disease, he said, with investigations focusing on the potential to slow down the development of early-onset Alzheimer’s.

The disease’s characteristic diagnosis is the accumulation of tangles and plaques in the brain over time.

Snell’s work, which he said could be a game-changer, focuses on what is known as the amyloid hypothesis, a process by which the amyloid protein sticks together to form clumps that later become plaques.

Understanding its effects is crucial to better understanding the disease. He said that until about three years ago, there was effectively no hope for Alzheimer’s patients. Work on the amyloid hypothesis is key to offering that hope, he said.

Russell Snell