Meghan Hawkes looks back to 1930 and reviews the stories making headlines in Waipā.

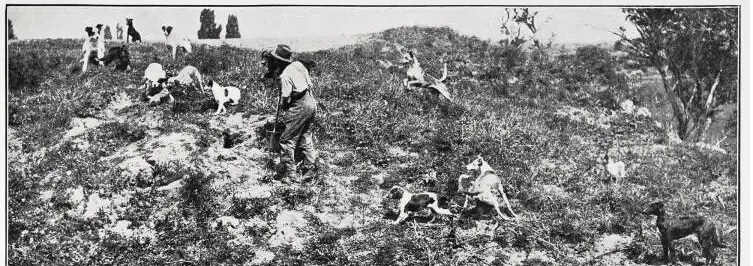

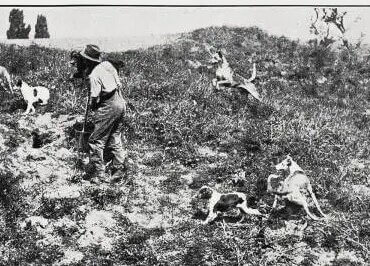

A rabbiter at a warren near Kihikihi

Rabbits had spread extensively in the Waipā region and property owners were expected to exterminate them to the best of their ability.

Rabbiters working with ferrets and large teams of dogs to flush out warrens were also employed by rabbit boards.

These were so successful that now there was a call for the amalgamation of the Rabbit Boards from Mangapiko, Hairini and Kihikihi.

The rabbit pest in the three districts had been so reduced that one board could administer the combined area.

Rabbits were believed to be very plentiful in all the back districts round Te Awamutu, but they were becoming few and far between, especially near the bush.

In the cleared lands there was evidence of a great horde of rabbits, but trappers operating there had considerably lowered the numbers.

Loud rumblings which sounded like distant thunder heard at Ōhaupō were accompanied by vibrations and assumed to be a rather severe earthquake.

But there appeared to have been no earthquake and the subterranean noises were difficult to explain.

Some residents heard the noises as a series of explosions a long way off which were sufficiently heavy to rattle windows.

They were inclined to associate the noises with Arapuni Hydroelectric Station although this was a considerable distance from the Ōhaupō area.

Arapuni itself experienced the strange noises and sensations the next day. While sitting at lunch about 1pm various Government officials thought they felt a slight earth tremor.

Professor Bartrum, Professor of Geology at the Auckland University College, eventually conceded “The rumblings seem almost definitely to be connected with an earthquake disturbance, apparently of local origin”. There were no known earth faults near Ōhaupō, the professor explained, but much of the district was covered by an alluvium – loose clay, silt, sand or gravel – which, in some places, was of considerable depth.

A bombshell fell in Pirongia when they received word from the Te Awamutu Borough Council that the rates for water from the borough main, which passed through Pirongia on its way from Pirongia Mountain, were to be increased.

Requests for the council to reconsider resulted in confirming the belief of consumers that they were not wanted, having served a useful purpose by assisting the borough scheme during the early years when water was running to waste.

Now, by eliminating the low-level consumer in Pirongia, in Mangapiko, and along the Frontier Road, the pressure to the new, and presumably more profitable, consumer elsewhere would be increased. Some of the consumers were faced with a water cost amounting to 10 shillings per acre per annum under the new charge. Wells, windmills, and tanks had been dispensed with and a return to this method of procuring water would be expensive and unsatisfactory. Fortunately, however, the Pirongia district had been endowed by nature with a pure and plentiful water supply.

A Te Rore ratepayer wanted a ranger to be kept permanently near the bridge to prevent stock straying on the roads.

Recently a motorist thought he saw a rut filled with water and went straight on, to find he had struck a large black pig. Around the same district quite a fair number of cattle were grazed all winter, and the authorities seemed to be quite indifferent to the danger. The Raglan County Council had put a pound keeper on the job after a horse, on a dark night, jumped on to the radiator of the car which a member of the council was driving near Te Pahu.