Craig Hoyle at Hautapu Cemetery.

Type the surname ‘Hoyle’ into the Waipā cemetery online database and several dozen names pop up.

When we meet, Craig Hoyle is standing in front of one of them at Hautapu Cemetery in Cambridge – his great, great grandfather Robert Hoyle, 92 when he died in 1963.

Craig Hoyle behind his great great grandfather Robert Hoyle’s headstone, buried hundreds of kilometres away from his wife Kate. Photo: Mary Anne Gill.

Robert, who emigrated to New Zealand as a teenager from Rochdale in Lancashire, England, had never “officially” joined the Exclusive Brethren but did so reluctantly when he was 90 so he could live in Cambridge with his sons William and Norman who were members of the church and farmed in the district.

He and wife Katherine “Kate” – who died in 1948 – had lived in Arapohue near Dargaville, another strong Exclusive Brethren community.

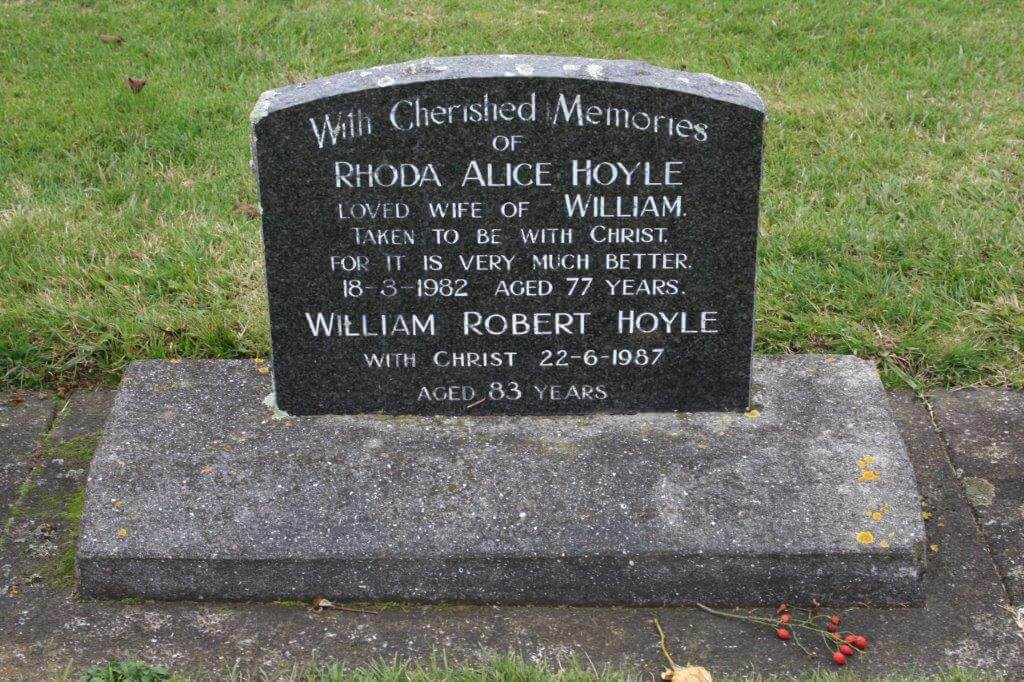

Craig spins around and points to the grave of his great grandparents William and Rhoda Hoyle, buried together and across to William’s brother Norman, excommunicated from the Exclusive Brethren because he refused to drink alcohol.

“Loving husband of Josie”, his tombstone says. If Craig were not there you would be hard pressed to know Eleanor Josephine Hoyle, buried in the next row, is the wife who walked out on him after 35 years’ marriage because he was no longer in the church.

Church rules forbade them being in the same plot, so Norman did the next best thing. He bought a plot as close as he could to her one, they are now only centimetres apart. Her stone does not reference her husband or the three children they had; his does.

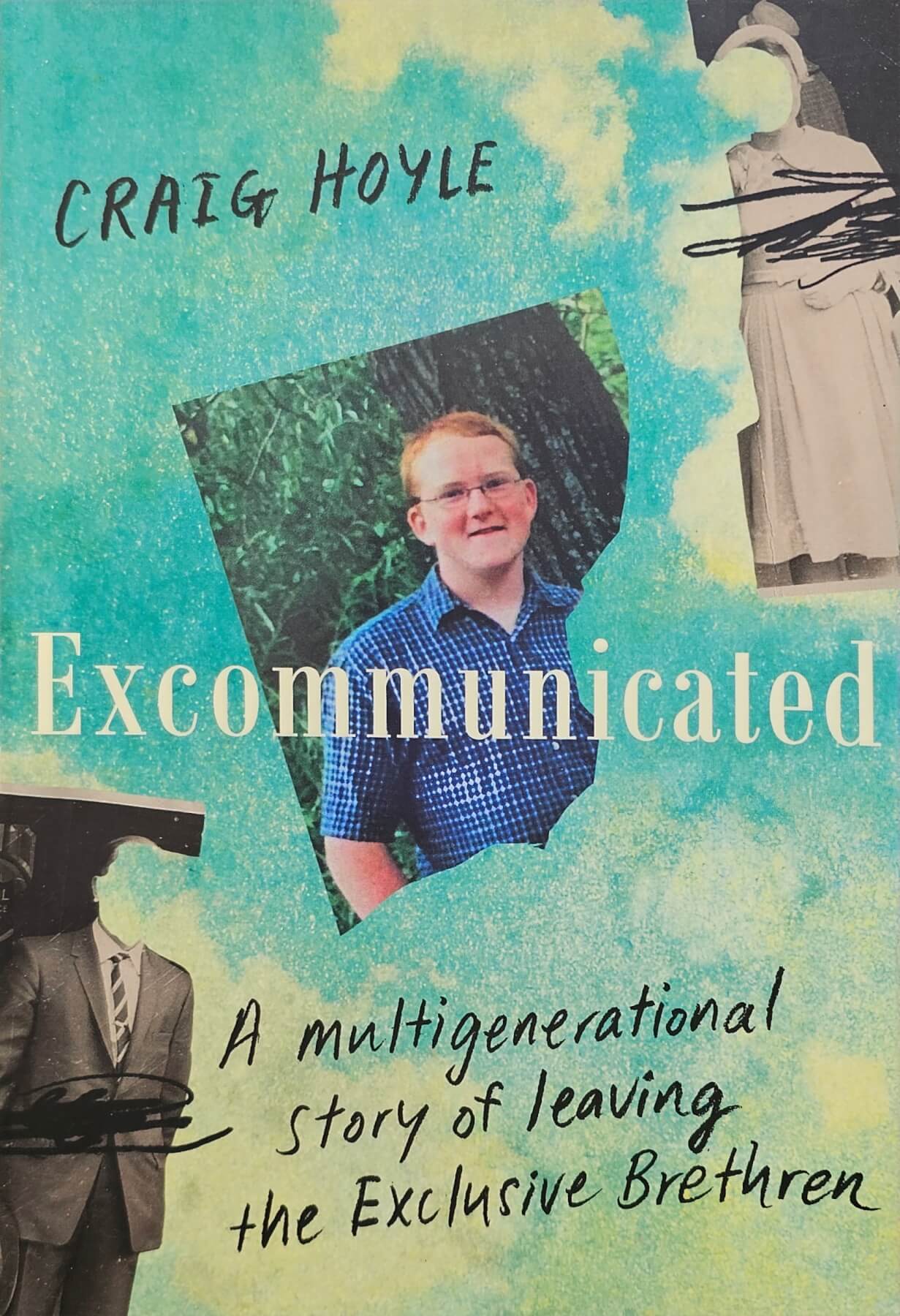

Excommunicated by Craig Hoyle.

Craig, 34, now a journalist in Auckland, was excommunicated from the Exclusive Brethren in 2009 because despite interrogations and conversion therapy for his sexuality, he remained gay.

He went on to make a television documentary with 60 Minutes. Reporter Sarah Hall, originally from Tamahere, and husband Grant became parent figures outside the brethren. They encouraged him to go to university and then to become a journalist.

He is ostracised by family members who are still in the church. They include his parents who, still reeling from the fact their son is gay, had to contend with him becoming a journalist as well.

“I grew up in a brethren where we weren’t allowed to challenge authority, we weren’t allowed to ask questions. We were told if you don’t understand it, don’t question it. We’ll do the thinking, you do the doing.

“Journalism is the opposite of that – journalism is about chasing the truth and asking the questions and exposing things that need to be exposed,” he says.

Any chance he had of reconciliation went out the window last year when Harper Collins published Craig’s story: Excommunicated – A multigenerational story of leaving the Exclusive Brethren.

Craig Hoyle at his great uncle Norman’s grave at Hautapu Cemetery with his estranged wife Josie buried the row in front of her husband, the closest they could get in death. Photo: Mary Anne Gill.

The book details four generations of the church’s presence in Cambridge and recalls a physical altercation with members at Rhoda Hoyle’s funeral in 1982 when her excommunicated eldest son Hubert “Snow” Hoyle tried to reach his mother’s graveside. There are other Cambridge stories.

The first edition sold out. Copies in Waikato bookshops, including Cambridge where there is a waiting list, went within days. There was a protest in Raglan – someone turned all the books upside down and turned all the covers in. The bookseller there reacted as only true book lovers do – they mounted a display of controversial books and planted Excommunicated in the middle.

Craig was born in Hamilton and moved to Invercargill when he was five. He spent many of his earlier years holidaying in Cambridge where he still has relatives.

“(My memories are) recent enough to still remember a lot of people but long ago enough now that I see people in the (Cambridge) street and I know they’re brethren and I know they are probably cousins of mine, but I don’t recognise who they are.”

For him there is an immense sadness.

“Look at my great great grandpa who was forced to join the church.”

Robert’s headstone is remarkably clean – others of the same vintage nearby are unkempt – leading Craig to assume there are mysterious church members who look after the outcasts or those separated from their loved ones.

William and Rhoda’s grave while not unkempt could still do with some attention. Craig feels guilty he did not bring flowers but then noted it is not something Exclusive Brethren encourage anyway.

William and Rhoda Hoyle buried together at Hautapu Cemetery.

“I see (their) grave, they had 10 kids, they lost four of them, four of them were excommunicated,” says Craig.

“The trauma everyone went through, even the ones who stayed in the church.

“The ones who leave are free to build a new life and come to terms with the way things are.

“The ones in the church I don’t think get a chance to grieve what happened because they believe they are doing the right thing. And they shouldn’t be sad about doing the right thing, but they are sad.”

In a brief meeting with his parents a few years ago, they asked Craig whether he still believed in God.

“I said I wouldn’t necessarily say that I believe in God as they understand God to be.

“But I believe in love and their Bible says God is love, so what’s the difference?”

Asked whether he thinks his great great grandparents Robert and Kate are somewhere together now, Craig has mixed views.

“I would hope that if they are anywhere, they are together and free of all the restrictions they lived with. There was so much control, so much fear.”

He hopes the same for all the Hoyles and their extended families whose names are littered throughout Hautapu Cemetery.

“There are Hoyles here who were in the brethren, there were Hoyles who were excommunicated from the brethren.

“I hope if they are somewhere that they are back together as one family. Not the them and us that they all suffered with when they were alive.”

Craig Hoyle looks across Hautapu Cemetery where the bodies of dozens of his family members are buried, including his great great grandfather Robert Hoyle. Photo: Mary Anne Gill.

When Harper Collins contacted Craig to write the book, he felt it was important to put the book out there for the record.

“One person’s story doesn’t capture the impact of a group like the brethren, because I’m just the result of what happened to my parents, their parents and their parents and (what) you can see walking around Hautapu Cemetery is that all these generations, after generations have been impacted by these restrictive religious rules. I just happen to be the latest chapter.”

Craig is in a relationship and has become a sperm donor.

“There are genetic progeny out there,” he says confirming there is at least one girl, born last year through the donor pool.

“It’s really meaningful to be able to go out and create new concepts of family, to contribute to new generations.”