Russ Rimmington and wife Edwina pictured with the Menin Gate buglers.

Stories abound of how a metal name plate or a coin in a wallet have saved the lives of soldiers.

On July 31, 1917, Arthur Maddox Major’s wallet was a simple leather bifold. If offered the young private no protection against a machine gun.

He had just written a letter home to his wife Gertrude in Dannevirke, announcing he was going into a huge battle.

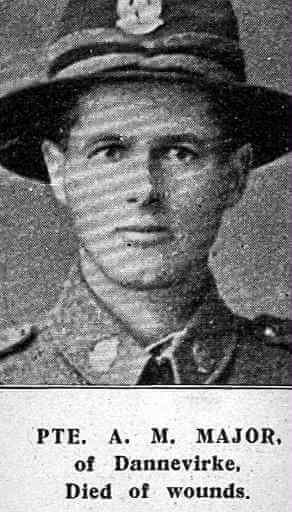

Arthur Maddox Major

Arthur Major died on the first day of the Passchendaele offensive in Belgium where the allies had launched a major offensive.

He had left Wellington on August 21, 1916, and arrived in Plymouth, England, in October – and his story was, tragically, the same as thousands of others.

By November 10, 1917, the third battle of Ypres had claimed 5300 New Zealand lives – and the death toll among armies under British command totalled 275,000.

More than a century later the wallet was placed on Major’s grave at Trois Arbres Cemetery, Steenwerck, France, by his grandson.

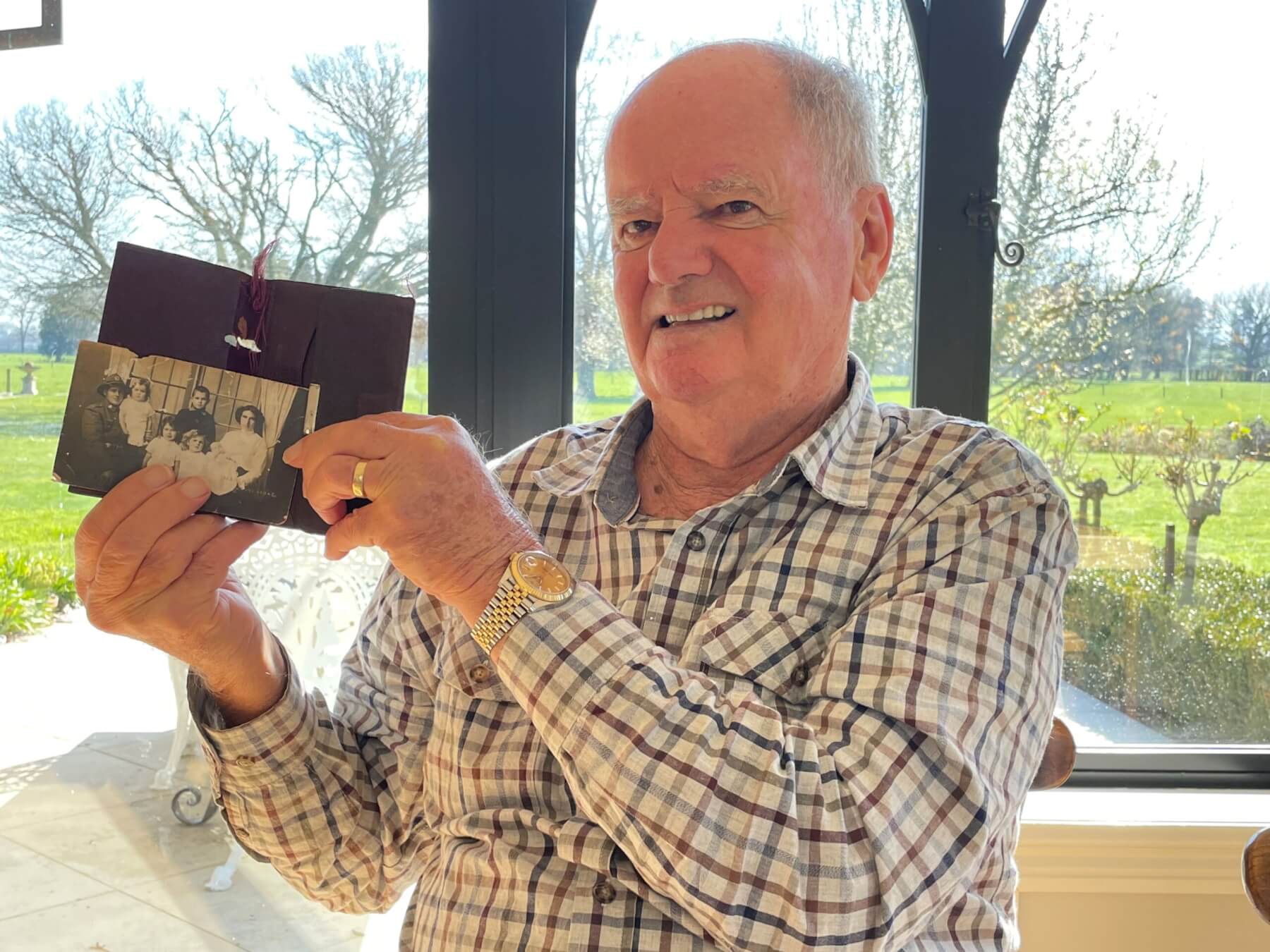

Tamahere dairy farmer and former local body leader Russ Rimmington and wife Edwina have recently returned from an overseas trip which included a visit to the cemetery.

It also took in time to visit the Menin Gate in Ypres.

Rimmington was also afforded the opportunity on July 7 to read The Ode, which is recited every day at the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres. The gate is dedicated to Commonwealth soldiers who fell there and those whose graves are unknown.

Six years ago, Rimmington read his grandfather’s final letter at the unveiling of a plaque at the Ypres Memorial Garden in Hamilton in 2014. The project was initiated by former city councillor Peter Bos.

Bos features in a book, which Rimmington brought home – with signatures of the some of the buglers who play as part of the reading of the ode ceremony each day. The book, produced by The Last Post Association – and with a forward by former British prime minister David Cameron – records the rebuild of Ypres after the first world war and the tradition which evolved at the Menin Gates from the first ceremony on July 2, 1928.

It was stopped only when the second world war broke out – but even then, buglers returned defiantly before the end of the war to remember the fallen.

Visiting the gravesite with the wallet more than a century later was moving, Rimmington told The News. It was also an opportunity to reflect on the horrors of the war – and the heroism.

- Menin Gate in Ypres.

- Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres

- Russ Rimmington at his grandfather’s grave, where he placed the 100-plus year old wallet.

- Russ and wallet