Treasure hunters at Lake Karāpiro.

Clams found in Karapiro shown with a $2 and $1 coin. Photo: Mary Anne Gill.

Thousands of invasive gold clams were found on Lake Karāpiro’s foreshore during the annual lake lowering on Saturday, 24 hours after they were designated an “unwanted organism.”

And the find has confirmed Karāpiro Domain site manager Liz Stolwyk’s worst fears on the eve of a season when user levels at the lake are expected to bounce above pre-Covid levels.

Stolwyk was given permission by the Ministry of Primary Industries (MPI) to collect a sample of clams for education purposes. The Waipā deputy mayor bottled them and later showed The News, council colleagues and staff.

Karāpiro Domain site manager Liz Stolwyk with clams she removed from the boat ramp on Saturday.

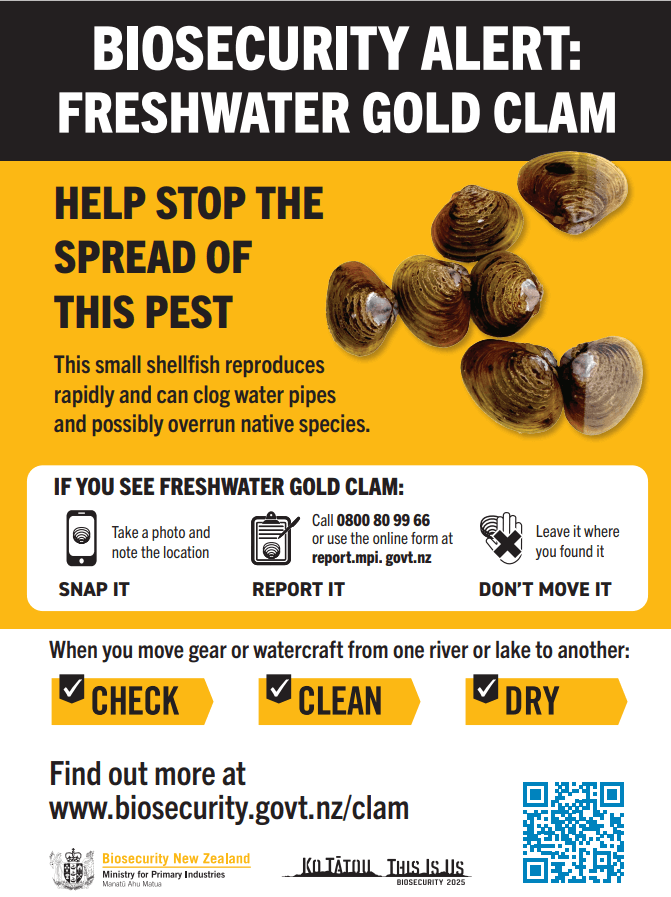

MPI declared on Friday the freshwater gold clams, first found at Bob’s Landing in May, are now covered by strict regulations under the Biosecurity Act. They revealed this in a freshwater gold clam newsletter sent out to subscribers.

Despite the enormity of the announcement, which threatens Waipā’s biggest visitor attraction, biosecurity minister Damien O’Connor did not issue a statement.

Stolwyk said she was disappointed at the lack of interest from national politicians suggesting it showed a lack of understanding at the implications of a gold clam spread.

She is working closely with MPI and other local politicians from Waipā, Hamilton and neighbouring local authorities.

The unwanted species status does not prevent people using the Waikato River for recreation. People must not knowingly move or spread the clams or water that may contain them.

Biosecurity New Zealand deputy director-general Stuart Anderson said MPI did give Ngāti Korokī Kahukura permission to remove clams for disposal.

Lake users must comply with Check, Clean and Dry conditions before moving their equipment or craft.

An “unwanted organism” is one that can cause harm to natural or physical resources such as rivers and lakes or human health.

The clams, native to eastern Asia, can produce up to 400 offspring a day and are hermaphrodites, meaning each clam has male and female reproductive organs and can self-fertilise.

Clams on the lake bed on Saturday. Photo: Supplied.

While Anderson says the clams could have been around for more than two years, treasure hunters on hand for the annual lake draw down on Saturday, say they were not there the same day last year.

They come to the lake with their scavenging equipment every year to dig and search for whatever gems lay under the water – lost by rowers, canoeists, water skiers and the myriad other lake users.

“The clams are everywhere (now),” said Stolwyk who was at the boat ramp to monitor the annual clean-up of jetties, retaining walls and lakeside equipment.

Anderson said an MPI staff member was also at the lake to promote the Check, Clean, Dry requirements and saw scattered patches of freshwater gold clams on the lakebed.

Clams picked up on the lake bed.

“They were lying in sediment alongside kakaki – the native mussels,” he said.

“Our focus has been on surveillance to establish where clam populations are present. As there is a known population in Lake Karāpiro, we did not conduct surveillance there at the weekend.”

Vehicles, equipment, tools, gear or clothing used on the day were subject to the new conditions which now gives MPI the opportunity to organise their response in a disaster-like way.

“It’s too early to understand what the impact will be. We don’t know how they live in our New Zealand conditions,” said Stolwyk.

“We’re doing absolutely everything we can. The risk right now is spread. We want to keep it out of places like Lake Taupō.”

She and MPI are organising events to educate Karāpiro users. They will be held at Horahora and Karāpiro domains and at Grantham Street in Hamilton where hundreds of school rowers train regularly.

MPI is holding a forum this week bringing together iwi, regional councils and Biosecurity New Zealand to “exchange ideas and share technical, scientific mātauranga Māori perspectives on the response to the freshwater gold clam,” said Anderson.

A Technical Advisory Group comprising domestic and international scientists and mātauranga Māori experts will continue to meet and build an understanding of the clam and potential options for controlling it.

Download frequently asked questions

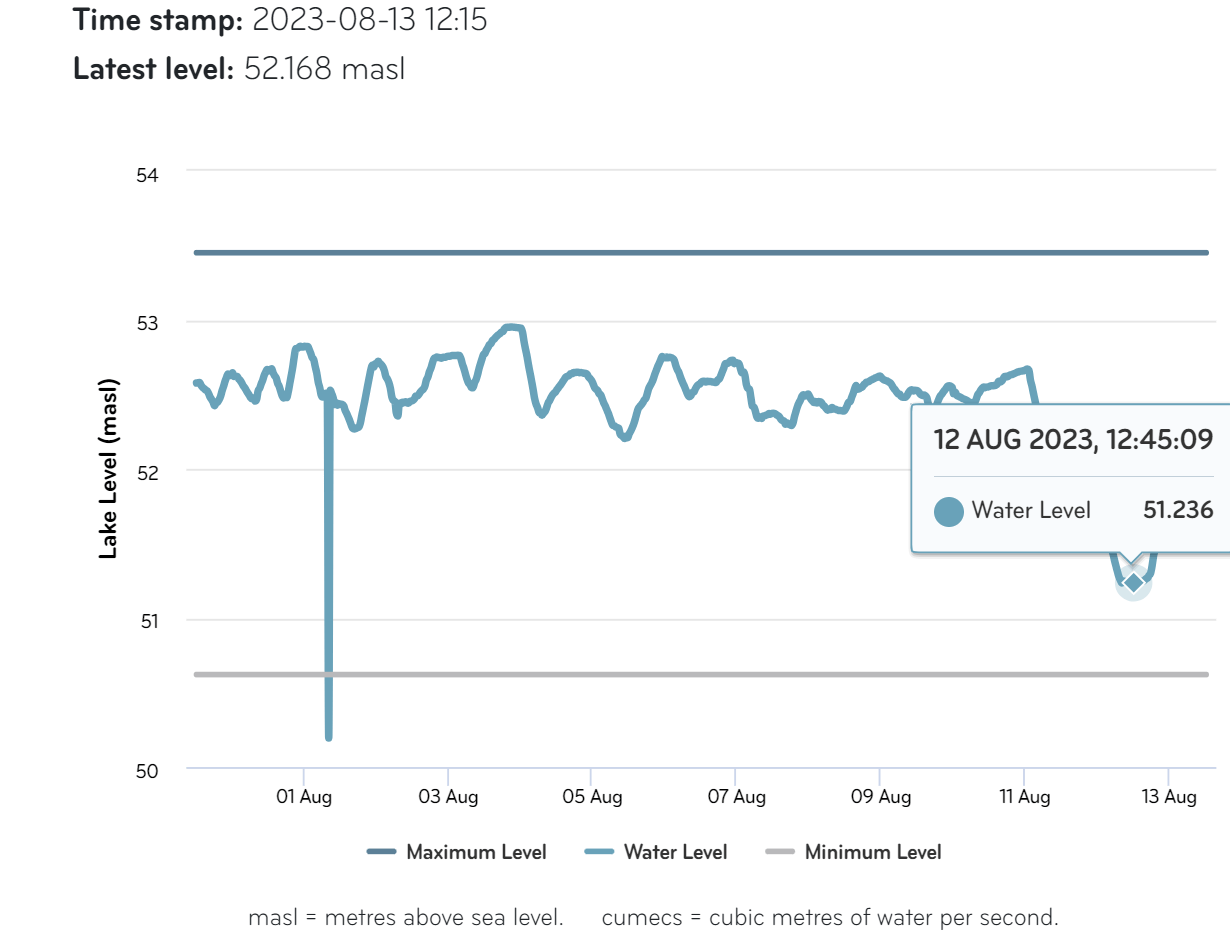

The lake level readings including Saturday 12 August.