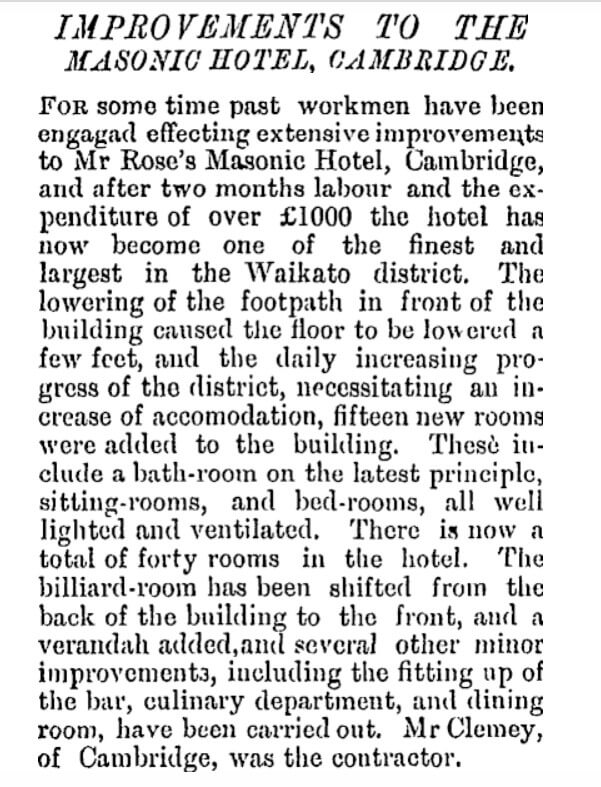

Masonic Hotel circa 1915-1925.

Mary Anne Gill documents the chequered history of Cambridge’s Masonic Hotel.

Masonic Hotel’s history has been a chequered one.

It was built of wood in 1866 on the current site. Sixteen years later in July 1882, it reopened after more than £1000 was spent adding 15 bedrooms – taking the number up to 40 – the billiard room was shifted from the back to the front and the bar was refitted.

Days later, the Cambridge correspondent reported the sad case of a hotel servant who denied to her workmates, employers and medical attendants that she was pregnant. Sarah Johnson said she merely suffered from an internal complaint. The police, acting on reports from other servants who heard the cry of an infant, went to a garden behind the hotel and discovered the body of a full-term baby boy buried behind a pig sty.

They subsequently found the woman had got up in the middle of the night, went to the garden and had the baby. She was arrested, charged with infanticide and appeared before a jury the next day. Dr Cushny carried out a post mortem examination and gave evidence, saying the child may have breathed once or twice but because of a physical defect, could not have lived. Sarah Johnson was found not guilty.

Then in October that year, the Auckland Star reported the hotel was broken into during the night and £2 in coins taken from the till. The Star further reported Constable Brennan took charge of the investigation and found a “native” named Te Rakatui, had changed a large number of threepenny pieces in a local store.

He was arrested on charges of breaking and entering and stealing money from the Masonic Hotel. But justice was swift in those days.

The magistrate dismissed the case saying hotel barmen had “sworn too positively” that the coins Brennan found on Te Rakatui when he arrested him were the same that were in the till. Te Rakatui was discharged.

But the most scandalous case came in June 1899 when William Carroll, the hotel licensee, assaulted his wife Elizabeth, 40.

She later died of her injuries, reported the United Press Association after “a shocking state of affairs”.

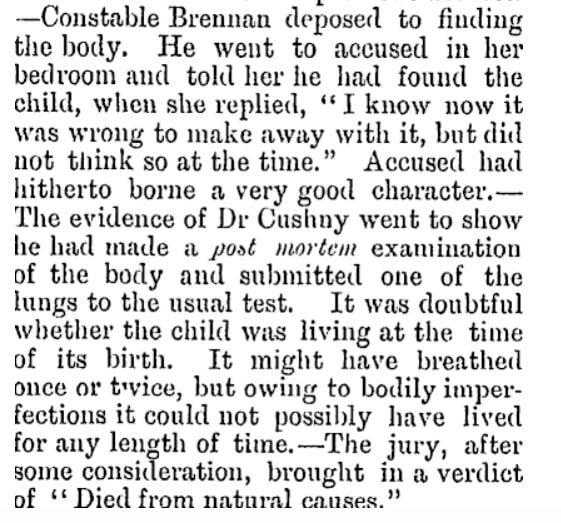

She is buried in an unmarked grave at Hautapu Cemetery.

Elizabeth Carroll’s unmarked grave between ‘Little’ Doris Chainey and Annie Forbes at Hautapu Cemetery. Photo: Mary Anne Gill

Rowland Makins, a horse breaker, gave evidence at the trial in June 1899 that he saw Mrs Carroll laying in the passage of the Masonic Hotel while her husband struck and kicked her.

Constable Cahill appeared and helped Carroll take his wife upstairs.

Other witnesses reported Carroll struck his wife three times while she was sitting in a chair. Her head struck the sofa and the next day she had black eyes.

The Supreme Court at Auckland heard in September the same year that the couple lived unhappily both in drink and out of drink.

A post-mortem revealed “shocking” injuries to Mrs Carroll’s body and three broken ribs.

Carroll said he had not intended to kill his wife. His lawyer argued because there was no malice, the charge could be reduced to manslaughter.

He was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

Early in the morning of 14 November 1911, the Masonic Hotel was destroyed by fire with guests escaping in their night dresses.

One ran to the fire station to raise the alarm but because it was raining, it was difficult for some members of the brigade to hear the bell.

The hotel was rebuilt to an Edwardian Classical design in brick by Fred Potts – Cambridge photographer Michael Jeans’ great grandfather – for £4100 and reopened in October 1912.

See: Millions for Masonic