Tuki’s 1793 map of New Zealand

The map of Waipā which adorns Garry Dyet’s office.

E te Tau 2022, ō mate, ō piki me ō heke, haere rā! E te Tau 2023 me tō pitomata, haere mai!

We’ve farewelled 2022, all of its ups and downs, and those who who have passed during the last year. Let’s welcome 2023 and its potential.

Histories of places, of the peoples of those places, how and why they are mapped I find fascinating.

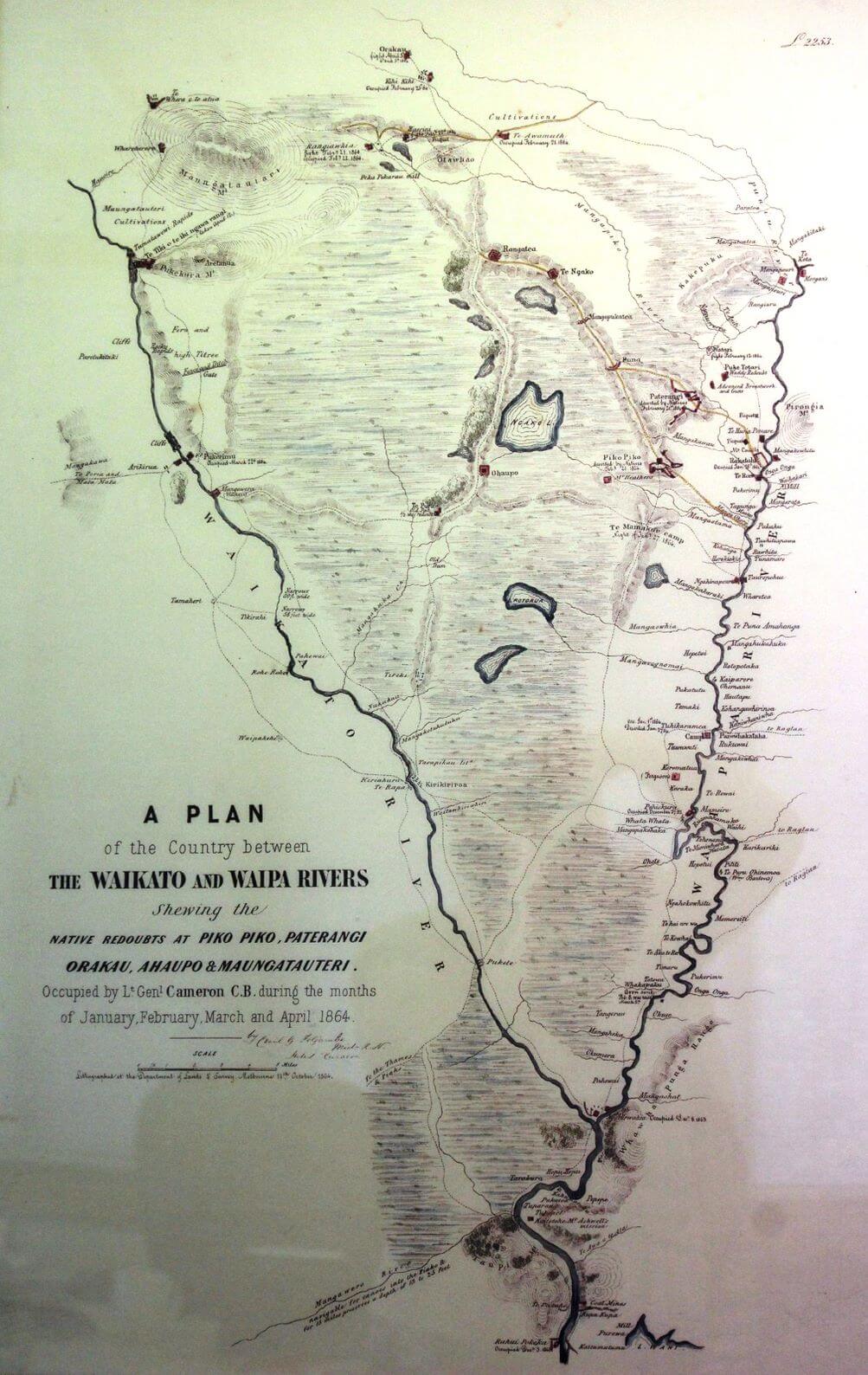

A map, on the wall in Gary Dyet’s office at the Waipā District Council dated 1864, is a case in point. In sharing this map with me our editor, Roy Pilott, has remarked that south is at the top of it, Hamilton is noted as Kirikiriroa, and there are details of pā in it (which may well be of interest to many of the News’ readership).

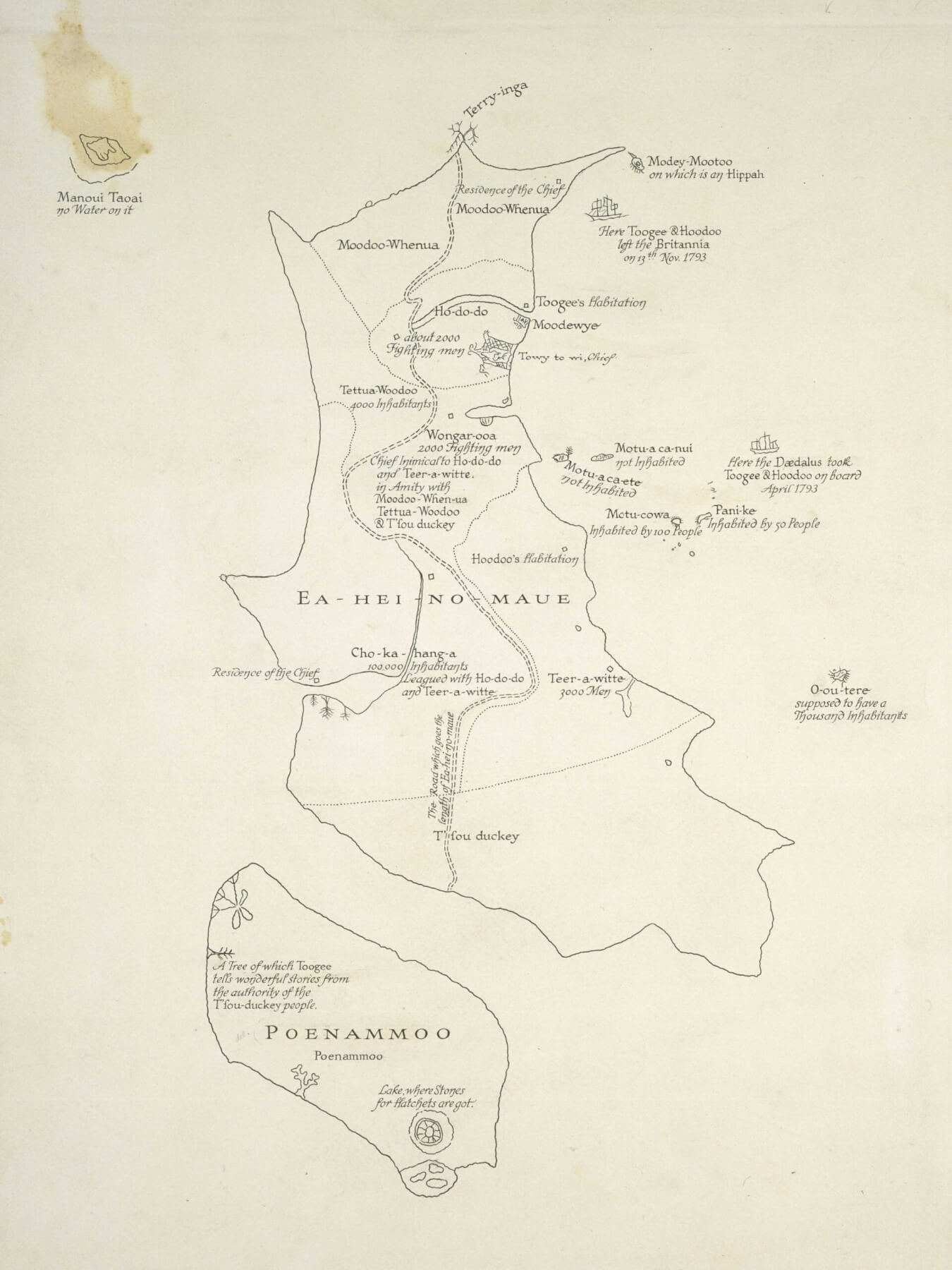

In this article I contrast that map with the map drawn by the northern chief, Tuki in 1793 for the Governor of New South Wales. At that time, British interests in New Zealand were included in the boundaries of New South Wales. Through his map Tuki provides for the governor an insight into Aotearoa – New Zealand from his world view, as he knew it. It would appear also that he was providing the governor with information helpful to the govermor in Britain’s interests in Ea-hei-no Maue (Te Ika ā Maui) and Poenammo (Te Wai Pounamu)..

He shows Poenammo (Te Waipounamu – the South Island) at the bottom and Ea-hei-no-Maue (Te Ika-a-Māui, the North Island) much larger on the top. This suggests to me that Ea-hei-no-Maue was of greater significance to him in terms of both its placement and its size. He no doubt would have explained to the governor the significance of his naming certain sites, and their importance socially, culturally, and politically to him and the information he wished to share with the Governor. Of particular note is the dotted line running through the North Island which marks the pathway followed by the spirits of the dead leading to their final leaping-off place at Terry-inga (Te Reinga) – the northern-most tip of the island.

The 1864 map carries an explanation informing the map reader of its being a plan of certain parts, what that plan principally ‘shews’, the timing of the drawing up of the map, and its authorship. Those explanatory notes of themselves beg a number of questions.

Discourse has been described as ‘verbal or written communication between people that goes beyond a single sentence.’ The overall meanings conveyed by language in context are part and parcel of a disourse. A map can be described as a ‘discourse’. The social, cultural, political and historical backgrounds of the map (the discourse): the reasons for its existence, the backgound of the author(s) of the map, and the persons or group for whom the map is intended are all part of that context.

The discerning reader of this article would do well to apply to this and any other article you read, simple principles of discourse analysis, which explore the discourse’s context. Key questions may well be – What is the aim of the author of the discourse? Who is the intended audience? What is used to achieve the author’s aims? What can be said about the power relationships intrinsic to the discourse? How successful is the discourse in acheiving the author’s aims?

Essential to discourse analysis is delving beyond what one sees on the surface of the discourse – into its context.

We each have our world views, some parts of which we share with others, some parts we do not. Reality in each of our social contexts is socially constructed.

Our experience of the world is understood from a subjective standpoint. Discourse analysis explores beyond the surface meanings of words and languages into how meaning is constructed in different contexts which include the social, cultural, political, and historical backgrounds of the discourse.

What these maps might mean to you will come primarily from how your social reality has been socially constructed. Our worlds are enriched by actively engaging with differing worldviews.

I would hope that, whatever might be your particular world view in perusing these maps, you might enjoy them in and of themselves, as part of our heritage as we move toward celebrating Waitangi Day in a few weeks time.

If you are of a mind to perhaps consider an analysis of the discourse, I would hope that an appreciation of these maps and their world views might also play a part in the celebration and exploration of our past, which can inform us of how we are who we are today, and also can be suggestive of who we might be in the future.

Paimārire ki a tātou katoa.

Dr Roa is a Tainui leader and Manukura/Professor in the University of Waikato’s Te Pua Wananga ki te Ao – Faculty of Māori and Indigenous Studies.